Women in ICT: Still wishful thinking or finally becoming a reality?

Authors: Chiara Longobardi Esposito Cesariello (DIGITALEUROPE), Wanda Saabeel (ICT Professionalism/ Eduserpro)

In the ever-evolving landscape of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), the need for diverse perspectives and talents has become more pronounced than ever. In the last years, the phrase “Women in ICT” has often been used from policy bodies to industry giants as a pledge aimed at addressing this disparity and unleashing the untapped potential of women in technology. The growing attention in promoting pathways for women to thrive in ICT roles is on the political agenda of almost all political bodies, organizations and industry. As technology continues to permeate every aspect of our lives and the market share of the sector in the global economy keeps rising[1], it is essential that women start playing an increasingly central role in the sector. Currently, women remain significantly underrepresented in this field. Although receiving significant attention in the realm of societal concerns and political agendas, the issue seems to linger. This raises the question: why does this challenge persist?

This article delves into the multifaceted aspects of this phenomenon, exploring the challenges faced by women in accessing and thriving in the ICT sector, the relevance of the matter and highlighting key initiatives that might drive the change.

The challenge

Our daily life is punctuated by digital services, tech devices, cloud spaces and apps. This not only implies a surge of the ICT sector[2], but also an ever-growing demand of related competences and professional roles. In addition, the demand for specialised skills is matched by the potential for new technologies to replace certain tasks and part of jobs, rendering them obsolete[3]. These factors contribute to create an even more complex scenario in the global market. How do women navigate this landscape, and to what extent do gender bias and inequalities shape their roles within it?

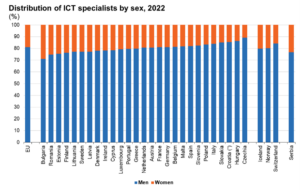

Europe is facing an unprecedented shortage of ICT professionals, with 55% of EU companies having difficulties recruiting ICT specialists in 2019, and women accounted only as 18.9% of specialists in 2022 (Figure 1)[4].

Figure 1. Eurostat: ICT Specialists in employment.

Among the EU Member States, the highest shares of women among employed ICT specialists were observed in Bulgaria (28.9%), Romania (25.2%) and Estonia (24.5%), while the smallest shares were observed in Czechia (10.9%), Hungary (13.6%) and Croatia (14.5%)[5]. When looking at more specific sectors, it is worth noting that in the EU just 16 % of all AI skilled individuals are women and 84 % are men[6], and only 25% of cybersecurity professionals are female[7]. The Digital Compass has set the target that the EU should have 20 million employed ICT specialists, with convergence between women and men, by 2030.

In terms of skills, the gap is significantly smaller for the use of internet and internet user skills. 85% of females used the internet regularly in 2020 compared with 87% of males. A 4-percentage-point difference can be observed in the digital skills indicators: 54% of females have at least basic digital skills (58% of males), 29% above basic digital skills (33% of males) and 56% at least basic software skills (60% of males) as of 2019.

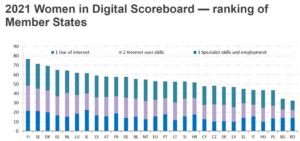

Women are the most digital in Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and the Netherlands. All these countries perform very well in DESI, too. Women in Romania, Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary and Italy score lowest on female participation in the digital economy and society (figure 2)[8].

Figure 2. European Commission: Women in Digital Scoreboard 2021.

An analysis[9] performed by McKinsey shows that if Europe were to increase the share of women in the tech workforce to about 45 % by 2027, it could both close the skills gap but also benefit from an increase in GDP of as much as €260 billion to €600 billion.

But if we would all benefit from closing the gender gap, then why it is so difficult to make it happen?

The pursuit of gender equality

It cannot be said that no attempts have been and are being made to address this. The striving for gender equality is and has been recognised an important topic for over decades. There are policies, strategies, guidelines and many initiatives, and gender equality is anchored in laws and regulations at national, European and worldwide level. This trickles down to the corporate level, where a growing number of companies have chosen to establish guidelines and directives related to the employment of underrepresented groups.

The European Union, which is committed to upholding and promoting the gender equality principle in all its actions, recently stressed the importance of women in ICT via ad hoc resolutions[10] and initiatives such as the Women in Digital Scoreboard, to monitor progress of member states in reducing the gender gap.

Furthermore, the EU formulated its 2020-2025 Gender Equality Strategy[11] and the topic is addressed in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[12]. Gender equality is a core value of the EU, a fundamental right[13] and a key principle of the European Pillar of Social Rights[14]. Likewise, the OECD considers gender equality a core value and a strategic priority.[15] Also, the topic has long been a focal point for the United Nations, which just recently launched a partnership[16] between UN Women and Women in Tech to empower women and girls in ICT across Europe and Central Asia.

Besides, the phenomenon is subject of study for decades of the interdisciplinary field of gender studies. Gender studies developed alongside and emerged out of women’s studies with roots lying in the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s. During this period, scholars began to question whether gender was a biological fact rather than a social construct. They argued that gender is a complex web of meanings and practices that are culturally constructed and reinforced through socialisation processes. The field of gender studies has further evolved and expanded to encompass the study of men’s roles and identities, the experiences of non-binary and transgender individuals, and the broader concept of gender as a social construct.

Concurrently, numerous non-profit organizations, associations, and civil society groups globally are aligning their efforts in pursuit of the same goal. The private sector has also played an active role in the past years, with companies such as Amazon, winner of Female Tech Employer of the Year in the Women in Tech Awards 2019 and partner of the WISE programme, and Microsoft with the Power Women in Tech Award[17] initiative and the Women in Business and Technology podcast[18] working to promote STEM careers for girls and women and boost their participation in the sector.

Recently, the narrative has taken more firm shape through the three closely linked values of diversity, equality and inclusion, or “DEI” for short[19][20]. Companies, investors, policymakers and wider society are increasingly paying attention to DEI in the workplace and in organisations. There are DEI programmes, DEI strategies, DEI policies and DEI measures all aimed at supporting different groups of individuals, including people of different races, ethnicities, religions, abilities, genders and sexual orientations.

This makes one wonder, how is it possible that the problem still persists despite all these efforts? The authors do not aim to fully unravel this, but only to provide a rough sketch that shows the complexity of the problem.

The complexity of the challenge

First of all, it appears that the problem is not limited to the ICT field alone. There is an overall underrepresentation of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (‘STEM’). The 2022 Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI)[21] reported a low rate of women with education in key digital areas. Only one in five ICT specialists and one in three STEM graduates were women. Despite the strides made in recent years, the issue persists.

When we capture the problem in terms of ‘gender equality’, it turns out to be even more encompassing[22]. EIGE’s gender equality index reveals a pessimistic view. Also, Sustainable Development Goal 5 concerns this very aspect and its status is shocking, according to the recently released report on it by the UN, describing the progress on the sustainable development goals[23]. Inequality based on sex is thus widespread in all parts of societies all over the world. Exceptions aside, of course.

The problem appears to be multifaceted, with many factors influencing it. All women find themselves subject to at least one, but probably more of these factors and they face a number of challenges or let’s just call them outright obstacles.

Social factors

Compared to their male counterparts, women tend to be more involved with household duties and spending more time on informal care for family members[24]. This causes them to have less time to devote to paid employment. A situation that strongly correlates to the social structure of a society or social group and the role men and women are expected to play in that society or group.

Cultural factors

There are stereotypes and cultural pressures that discourage girls to pursue a professional role in the area of STEM, and develop the skills needed to become a professional in STEM-related areas, including one as an ICT professional. To this day, technology including ICT is still seen as “toys for boys”, related to the fact that preconceived ideas of how women and men use technology remain unchanged. The idea that technology is a boy’s domain already starts from a young age. Boys and girls tend to be treated differently by parents, teachers, and carers.

This different treatment of boys and girls is deeply rooted in societal preconceptions, which are ingrained in us from a young age. It is known that parenting plays a formative role in the indoctrination of gender roles from infancy[25]. Parents make lasting decisions regarding a person’s gender identity from the time of birth, dictating the child’s activities and preferences. This indoctrination of societal norms continues when the child enters the school system and an environment is created that can be damaging to the self-confidence of women and men alike. It is these kinds of stereotypes that influence the choices girls and women make, reduce their confidence and interest in ICT and turn them away from ICT as an occupation.

Organisational factors

The ICT sector is widely known for being male-dominated and similar to other typical ‘men’s professions’ dominant male work practices are hostile environments to women[26]. This situation undermines women’s entry into ICT education and employment as well as hinders them in the performance of their work, losing their drive to excel in their profession because of obstacles such as discrimination, stereotyping, prejudice, and lack of opportunities.

Support and role model factor

Another important factor often mentioned is the lack of female role models. There is a need for more women in executive roles, more inspiring role models and more female mentors[27]. Stereotyping and the lack of support during schooling, especially by female teachers and mentors are considered big barriers.

Clearly, this problem is not caused by a few superficial issues that are easy to change. The problem is not only multi-faceted, but also multi-layered and deeply rooted in our systems.

The way forward

The European Commission in its document “Digital Decade Cardinal Points”[28] stresses that ICT specialists or sector specialists with advanced digital skills cannot be made overnight. The EC mentions that evidence shows that pupils who are involved in the learning of coding or computational thinking from an early age are more likely to continue studying ICT or digital-related fields. The EC currently applies three main educational approaches across the EU to boost digital skills including the (a) cross-curricular approach (aims at having students develop digital skills in all/multiple subjects), the (b) approach to introduce a separate subject (e.g. informatics, also known as computer science) as well as the (c) approach to include digital skills in an already existing subject (e.g. science). Whereas each approach is valid, making informatics a compulsory subject has the advantage to offer the possibility to all students to develop digital skills, potentially increasing their interest in STEM and digital disciplines, and reducing the gender gap.

Education is considered key which is why we advocate including the topic of gender equality in several ongoing European projects such as ESSA, ARISA, Cyberhubs, and Digital4Sustainability and focusing on it separately. Within each of the areas these projects focus on, people need to upskill and reskill. We see it as a challenge to pay separate attention to how the position of women can be strengthened in each of these areas. For instance, interviews with female role models could be considered. Learning units and materials can also be developed that can easily be embedded in new or already existing courses, training programmes and curricula in all or multiple subjects, in line with the aforementioned cross-curricular and other approaches.

An important starting point here is the development of π-shaped and comb-shaped professionals who are not only experts in ICT but also in another field, such as finance, retail, marketing or any other field. It is these kinds of professionals that can bridge the differences between those fields. This would be an ideal role that women could fulfil, given the fact that many ICT specialists are unable to cross the border of their profession. For women this could be an opportunity. Recommendations in this direction have already been made by giving digital skills and ICT a permanent place in training and education in other disciplines.

If women can form that bridge between two disciplines, the results of ICT projects, for example, are expected to go up, in analogy with the performance of organisations where women are part of the primary business process in e.g. a project team or are part of the management team or board of directors. Diverse perspectives and skills lead to more creative teams and increase companies’ wellbeing. It has been proven that the most gender-diverse companies are 48 percent more likely to outperform the least gender-diverse companies[29].

In conclusion, the vital role of women in the field of ICT cannot be overstated. Their participation not only promotes diversity and inclusivity but also drives innovation and economic growth. By fostering an environment that encourages and supports women in ICT, we can exploit the full potential of technology for the benefit of society as a whole. It is essential that we continue to advocate for equal opportunities and representation, ensuring that women thrive and progress in this rapidly evolving field.

[1] https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/europe-ict-market

[2] Eurostat, ‘ICT sector – value added, employment and R&D’, February 2022. For a specific overview of the value added of the EU’s ICT sector, see at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=ICT_sector_-_value_added,_employment_and_R%26D#The_size_of_the_ICT_sector_as_measured_by_value_added

[3] EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service, ‘The impact of new technologies on the labour market and the social economy’, Feruary 2018. See at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/614539/EPRS_STU(2018)614539_EN.pdf

[4] Eurostat, ’ICT Specialists in Employment’, May 2023. See at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=ICT_specialists_in_employment#ICT_specialists_by_sex.

[5] See note above, for the data by year, consult: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/isoc_sks_itsps/default/table?lang=en

[6] EIGE | European Institute for Gender Equality, ‘Artificial intelligence, platform work and gender equality’, 2021. See at: https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/mh0921386ena_002.pdf

[7] Cybersecurity Ventures, ‘Women in Cybersecurity 2022 Report’, 2022. See at: https://cybersecurityventures.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Women-In-Cybersecurity-2022-Report-Final.pdf

[8] European Commission, ‘Women in Digital Scoreboard 2021’, October 2021. See at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/women-digital-scoreboard-2021

[9] McKinsey, ‘Women in tech: The best bet to solve Europe’s talent shortage’, Sven Blumberg, Melanie Krawina, Elina Mäkelä, and Henning Soller, 2024. See at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/women-in-tech-the-best-bet-to-solve-europes-talent-shortage

[10] European Parliament, resolution of 21 January 2021 on closing the digital gender gap: women’s participation in the digital economy (2019/2168(INI)). Plus, European Parliament resolution of 10 March 2022 on the EU Gender Action Plan III (2021/2003(INI)).

[11] European Commission (2023). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – A Union of Equality: Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025. COM(2020) 152 final. Brussels: EC.

[12] European Commission (2012). Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), Official Journal C 326, 26/10/2012 P. 0001 – 0390.

[13] See Articles 2 and 3(3) Treaty on European Union (TEU), Articles 8, 10, 19 and 157 TFEU and Articles 21 and 23 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

[14] European Commission, DG Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion: European Pillar of Social Rights – Building a fairer and more inclusive European Union, see at: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1226&langId=en

[15] OECD (2023). The OECD’s Contribution To Promoting Gender Equality. Meeting of the OECD Council at Ministerial Level Paris, 7-8 June 2023. Paris: OECD.

[16] See at: https://eca.unwomen.org/en/stories/news/2023/05/press-release-un-women-and-women-in-tech-partner-to-empower-women-and-girls-in-ict-across-europe-and-central-asia#:~:text=UN%20Women%20and%20Women%20in%20Tech%20will%20cooperate%20to%20increase,with%20governments%2C%20private%20sector%2C%20development

[17] https://pulse.microsoft.com/en/transform-en/na/fa3-microsoft-power-women-in-tech-award-power-success-spark-inspiration/

[18] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/women-in-business-technology

[19] Edmans, A., Flammer, C. & Glossner, S. (2023). Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. ECGI Working Paper Series in Finance. Working Paper N° 913/2023. European Corporate Governance Institute.

[20] McKinsey & Company (2022). What is diversity, equity, and inclusion?

[21] Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), July 2022. See at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2022

[22] European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) (2020). Gender Equality Index 2020: Digitalisation and the future of work. Vilnius: EIGE.See at: https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/toolkits-guides/gender-equality-index-2020-report/men-dominate-technology-development?language_content_entity=en

[23] UN Women and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division (2023). Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals – The Gender Snapshot. New York: UN Women. See at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/09/progress-on-the-sustainable-development-goals-the-gender-snapshot-2023

[24] Musungwini, S. e.a. (2020). Challenges facing women in ICT from a women perspective. Journal of Systems Integration 2020(1). 21-33.

[25] Gupta M., Madabushi J. S., Gupta N. (2023). Critical Overview of Patriarchy, its Interferences with Psychological Development and Risks for Mental Health. Cureus. 15(6): e40216.

[26] Howcroft, D. (2019). Striving for gender balance in the IT industry. On Gender. The University of Manchester. 18-19.

[27] González-Pérez S., Mateos de Cabo R., Sáinz M. (2020). Girls in STEM: Is It a Female Role-Model Thing? Frontiers in Psychology. 11(2204).

[28] European Commission (2023). Commission Staff Working Document – Digital Decade Cardinal Points. Accompanying the document: Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Report on the state of the Digital Decade 2023. SWD(2023) 571 final. Brussels: EC.

[29] McKinsey&Company, ‘Diversity wins: How inclusion matters’, 2020. See at: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters